Racing animal welfare remains our top priority

Former QRIC Commissioner Ross Barnett, 2019

This is an extract from the belatedly released official Stewards Report from the Morven race meeting at Saturday at which three horses died, in unrelated circumstances according to the QRIC.

As you can see, it is clear from the report that the race day Stewards had concerns about the safety of the track after a previously healthy young 4-year-old horse named Pucker Up Palmer faltered after the winning post in race three, and suffered an injury so bad that the vet had to kill it to put it out of it’s pain.

The stipes ordered the Morven club officials – all three or four of them – to rectify the track surface before the next race, to improve it’s consistency.

Apparently through some miracle in the space of the 25 minutes between weigh-in and the horses going out for the next race they did.

According to the Stewards anyway.

There were only two stipes on duty at the meeting.

They had to hand out saddlecloths, check brands and numbers in the parade ring, weigh the jockeys in and out, take post race swabs, and get to their towers or positions before the next race started.

How on earth could they have had time to walk the track to inspect it to see if it was safe prior to announcing that it was?

Simple answer?

They couldn’t have.

My bet is that relied on the word of the club officials that it was okay, or at the very best only inspected the discrete section of the track where the now dead young horse broke down.

That is not good enough, not good enough at all, which leads to another important question.

Did the Stewards inspect the track to ensure it was safe to race on before the meeting commenced?

If so, then

(a) When?

(b) Which one of them conducted the walk and inspection?

(c) How did that official miss the unsafe sections of the course proper that were responsible for the horse’s untimely deaths?

(d) What qualifications and training do these Stewards, and indeed all of the stipes employed by the QRIC, hold that enables them to make such assessments of the safety of race tracks with surfaces that vary from sand to red dirt to oil based dirt to turf to tapeta and beyond?

(e) What training does the QRIC provide them with to gain such skills?

There are further questions from an animal welfare perspective as well.

(f) What facilities or equipment does the Morven track – and indeed all small country town tracks – have to enable them to make proper assessments of injured horses and/or save their lives?

(g) Is there a horse ambulance, or any other form of transport to a vet surgery for injured horses?

(h) Is it appropriate for the QRIC to engage young first year vets fresh out of university to act as the race day veterinarian and be placed in situations like this where they are forced to make life or death decisions about injured horses?

(i) Why is the QRIC employing first year vets with no more than 8 months professional experience and a special interest in small animal surgery and cattle to officiate at horse racing meetings?

(j) Why in this case did the QRIC engage a vet from Roma which is 180km away to officiate at the meeting, when there a number of vets in Charleville which is only half the distance away?

This is by no means any criticism of the young vet on duty at the races, who I am sure performed their duties to the best of their ability and experience, and with diligence and professionalism.

But three horses have died here, and ensuring the highest standards of animal welfare protection is one of the three paramount and overarching objectives of the QRIC.

In fact it is why the organisation was created.

So they are questions that must be asked.

These that follow below must be asked too.

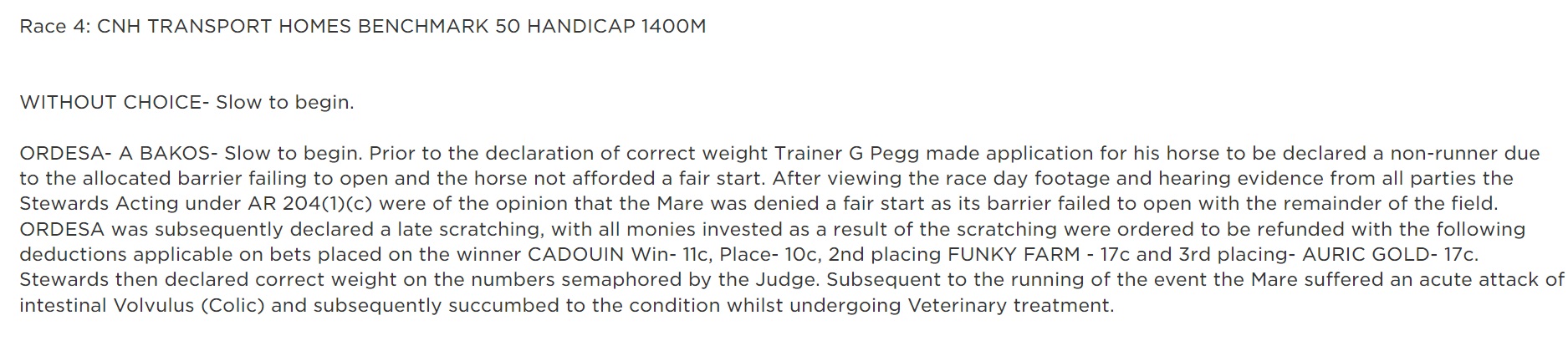

Both Commissioner Gillard and the Steward Report have told us that a 7-year-old mare named Ordesa, who was declared a non-runner after its barrier failed to open in the fourth race, suffered an attack of acute intestinal volvolus (colic) shortly after returning to the paddock, and died whilst receiving veterinary treatment.

(k) Is the QRIC aware that the onset of colic within just minutes of racing is extraordinarily rare?

(l) Is it aware that the clinical symptom of an acute attack of colic is extreme abdominal pain of a type that is the worst a horse can suffer?

(m) Does the QRIC agree that, notwithstanding it’s subsequent declaration as a non-starter, the horse Ordesa could not have competed as it did in race 4 at Morven if it had been suffering from an colic attack, or indeed even have cantered to the barrier without displaying extreme signs of distress?

(n) Did Ordesa display any such signs prior to being loaded into the barriers, or during the race?

(o) If so, why was the mare permitted to start?

(p) If not, is the QRIC aware that sudden equine deaths within an hour following an attack of acute intestinal volvulus are so rare as to be statistically highly improbable?

(q) Given that untreated colic is one the leading causes of death in horses, what equipment did the vet at Morven – and indeed vets at all race tracks under QRIC’s control – carry on race day to treat such conditions?

(r) How was it possible that the race day vet at Morven was able to diagnose the cause of death of Ordesa as being acute onset intestinal volvulus when confirmatory tests are required in order to do so?

(s) What treatment was the mare actually being given prior to her sudden death at the track?

(t) Did Odesa actually die of natural causes, or was she in fact euthanised?

(u) If the latter, why given that 35 to 60 percent of horses that suffer from this condition can be saved by surgery?

(v) What veterinary facilities were available to the on course vet to perform immediate surgery on Odesa, and where are they located.

In posing these questions I again wish to stress that we make no criticism of the work of the on-course vet.

Animal welfare is however by the QRIC’s own repeated declarations the organisation’s highest priority.

When such statements are made it is incumbent on the organisation that makes them to walk the talk.

Has QRIC walked it?

Does Queensland racing walk it?

The jury is well and truly still out.

—————————————-

Queensland Racing Integrity Commission (QRIC) Director of Veterinary Services and Animal Welfare Dr Martin Lenz is sending a timely reminder to all trainers and owners about the importance of caring for greyhounds around the clock.

Dr Lenz said insufficient care and attention can have severe consequences on the health of greyhounds, even resulting in death.

“It is really important that greyhounds are monitored regularly, in particular after they eat, to make sure they are acting normally,” he said.

“Being a deep-chested breed of dog, greyhounds are more prone to suffer from conditions such as ‘bloat’ after eating, potentially leading to dire consequences, if not attended to immediately. In this condition, the stomach distends and can twist on its axis, leading to a rapid deterioration in the dog’s state of health.

(Editor’s note – the condition that Dr Lenz is describing are near identical to intestinal volvulus)

“However, if the dogs are monitored, it becomes obvious that the dog is uncomfortable, and that something might be wrong.

“In these situations, only early veterinary diagnosis and surgical intervention can save the greyhound’s life, so it is vital that all owners and trainers monitor their dogs, especially after eating.”

Dr Lenz said it is important that owners and trainers follow a strict routine of feeding followed by toileting/check-up later in the evening before checking on their dogs again early in the morning each day of the week without exception.

“It is in everybody’s interests that animal welfare is the top priority for the greyhound racing industry, as the standards of animal care and welfare can have a profound effect on public perception of the sport.

“The Commission continues to make concerted efforts to ensure that optimum care is provided to all racing animals.”